Richard Rezac “Setting”

2023. 4. 9 Sun - 5. 14 Sun

Opening reception 2023. 4. 9 Sun 14:00 - 17:00

Setting consists of eight artworks made between 2008 and 2023 in the artist’s Chicago home-studio. They are slowly and carefully rendered from a variety of materials, including aluminum, bronze, paint, maple wood, cherry wood, and cotton. Much like a small, plein air easel painting, the artworks appear perfect from across the room, but come into focus as imperfectly handmade in closer proximity. The materials are cut, cast, sanded, and painted, but always – in some measure – permitted to be themselves: the unevenness of a painted, wooden surface, for example, is critical to the work’s character and code. These are not illusionistic artworks, but instead experiments in color, shape, scale, form, perception, and geometry, and are human in scale.

In the past, most works were untitled; now about half carry titles. Of the eight artworks presented in Tokyo, six are titled.

Thorax (corner) consists of partly suspended and lopped off oval bronzes attached to a white, wooden corner construction.

Tendril (Thomaskirche) is two cylinders of cast, untreated bronze positioned vertically against connected panels of dark green wood. Four coat hanger-like appendages emerge horizontally from the metal.

Plat is a shiny wall-mounted bronze. Its modest iridescence reflects the room in various colors, nearly psychedelic, and is due skin contact.

Chigi, Pamphili is suspended from the ceiling. Silver, yellow, white, orange, green, circle, square, rectangle, bulbous, rigid, aerodynamic.

The bronze and lavender work is Laterano frame. The bronze is untreated, the fire scale of the casting process visible in its color, texture, and overall feel. Repeating shapes skip across its façade.

Breath (Loschenkohl’s Mozart) is a sculpture in two parts: a large, chin-like chunk of aluminum with a small, bronze vanity-like form above. The chin resembles a fragment, the vanity a relic.

Untitled (15-04) is two diamonds of painted cherry wood – light green and dark blue – partly surrounded by cut aluminum.

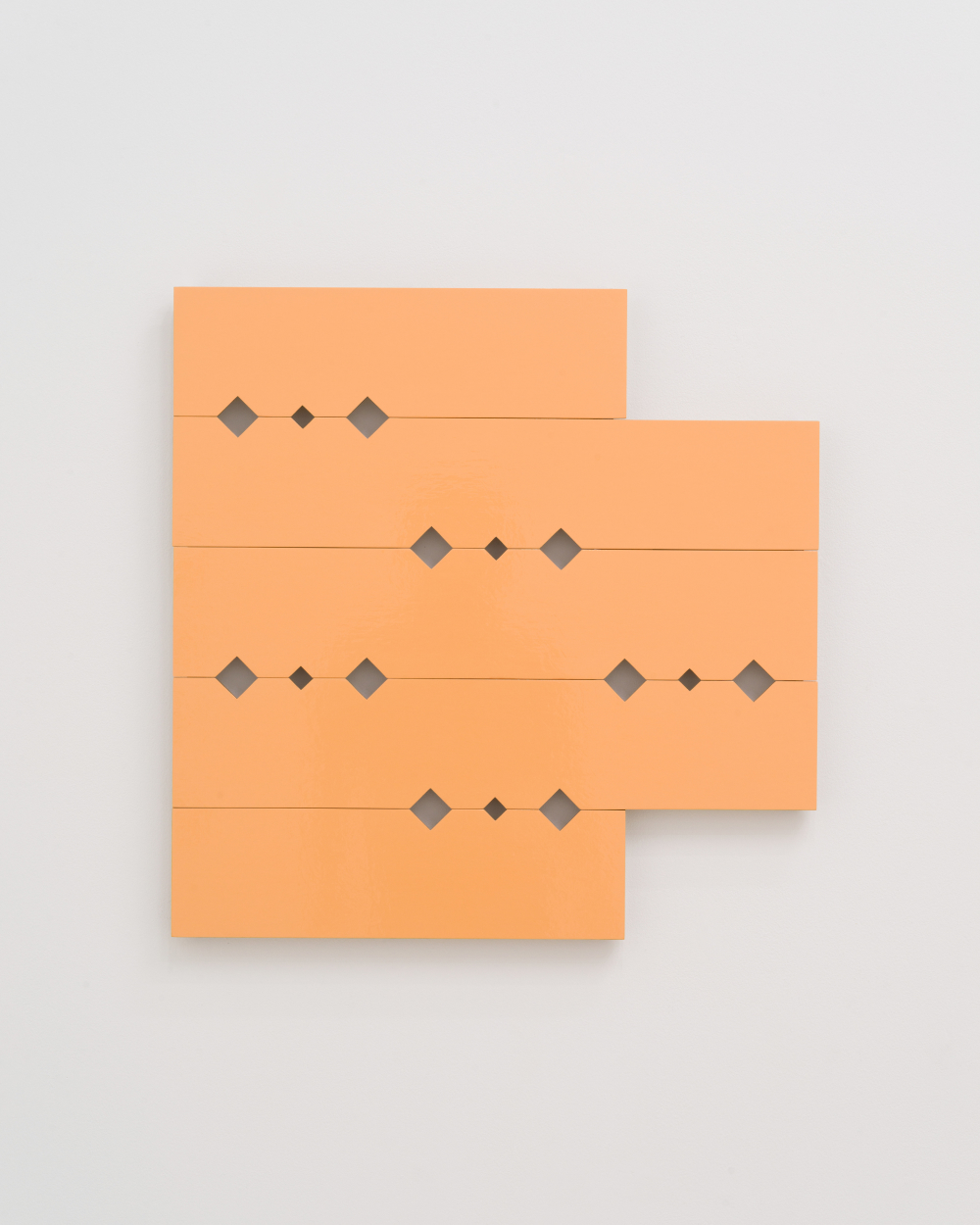

Untitled (08-06) is made of five pieces of horizontal wood painted in light orange. Two differently-sized diamonds are made from negative space. The glossy paint employed in and elsewhere serves to complicate a singular perspective or experience of the work. The piece partly reflects the world around it, and resembles a graphic score, or slatted building materials.

The artist uses language to signal conscious points of reference or inspiration, and the titled works bear a different charge for the artist; not a better or richer charge, but simply a distinct one.

Thorax for its relationship to the body; Tendril (Thomaskirche) for a church in Leipzig; Plat for an overhead map that indicates discrete parcels of land; Laterano frame for an ancient Roman basilica church; Breath (Loschenkohl’s Mozart) for the Viennese engraver who rendered Mozart in silhouette; Chigi, Pamphili from the family crest of one of the chief patron families of the Italian Baroque architect Francesco Borromini.

The untitled works employ parentheses, and are named for the year and sequence they were created.

While Rezac’s linguistic associations may conjure a deeper or more multi-faceted experience in some viewers, the artworks simultaneously suggest that geometry is sacred in and of itself, an autonomous force, sign, or gateway to understanding. I’m not certain that these are opposing ideas.

***

I watch a YouTube video of Rezac’s 2016 lecture at the Art Institute of Chicago – an event I initially attended in person – in preparation for writing this statement. I am waiting for one moment in particular that I remember.

From his place at the podium, Rezac broadcasts a black and white image of his parents on the projector screen. They are standing in front of their garage in Nebraska; it is 1949, three years before he is born. There is an uncommonly mysterious and attractive reflection across the small, patterned garage window.

Richard speaks of his desire to reproduce the window and its reflection as an artwork; not as an image, but in relief. He shares a photograph of Nemaha (2010), the finished piece, named after the street his family lived on. It is nickel-plated cast bronze, and extends from the wall in correspondence with the light and shadow of the original photograph, affording literal dimension to a memory that’s not quite his, but nonetheless all his own.

My phone rings, and it’s my mother, calling from south Florida. I have waited to arrive at precisely this point in the lecture, and am curious to how the artist will pivot to his next slide, his next incarnation. But here’s my mother, sandwiched somewhere between two and three dimensions, glowing up at me from my desk. I answer it, and there she is. How are you?

Text by Jordan Stein